Children in detention: A government without compassion

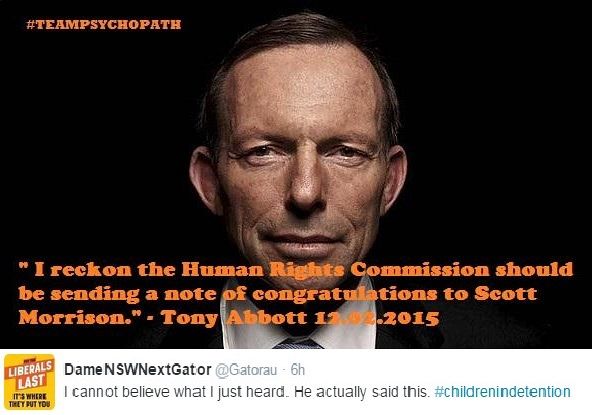

Prime Minister Tony Abbott dismisses a damning Human

Rights Commission report into children in refugee detention, saying he

feels no guilt about their plight whatsoever. Human rights lawyer Joshua Dale says there needs to be complete overhaul of attitudes amongst Australia's politicians and their constituents.

IT IS with sadness, that one must now accept that the rights of

children in Australia, particularly so far as it concerns Australia’s

immigration policies, have fallen by the wayside.

There is now a common theme amongst Australian governments to dismiss

human rights issues when it concerns Australia’s detention facilities

and the treatment of their occupants.

Recently, the Australian Human Rights Commission under the guidance of its president, Gillian Triggs, has engaged in a national inquiry

into children in immigration detention. The report has now been

released, making 16 recommendations, including that all children should

be released from detention in the next four weeks and that a Royal

Commission into the treatment and detention of children should be

convened.

This report has been met with strong opposition by the Abbott Government.

The Federal Government’s current approach to ensuring Australia’s

international obligations are upheld is by delegating authority to the Australian Human Rights Commission to investigate and advise.

Outside of the Human Rights Commission's recent findings, there

remains the question of how children or minors accused of people

smuggling are affected by current Government policies.

You may recall reports in 2012 and also 2013 where young Indonesian children, accused with people smuggling crimes, were detained in Silverwater Prison.

Many of these children came from impoverished backgrounds, in which

they were forced into operating vessels on the high seas where they

risked death, all for the purpose of being able to return what can only

be described as a dismal income to their families. Evidence submitted to a Senate Inquiry suggested that many of these individuals had very little knowledge as to whether or not they were, in fact, committing a crime.

When detained in Australia, many of these minors did not have any

identification or birth documents in their possession. In the absence of

identification data, their age was determined by the performance of a

wrist X-ray, which would then be examined for certain levels of

deterioration in the wrist, which could then estimate age of the minor.

Various studies had been in existence prior to the implementation of

law that allowed for age testing with the use of X-ray. These

anthropological studies concluded that there existed a significant

variation in findings and concluded that unreliable results concerning

bone ages had arisen. The conclusions generally were that the testing

methods did not accurately represent multi ethnic child populations.

For example, a study conducted in 2001 [Mora Et Al, “Skeletal Age Determinations in Children of European and African Decent; Applicability of the Greulich and Pyle Standards”, Paediatric Research

(2001) 50, pp624-628] indicated that African American children had a

greater bone age than those of European decent. The testing standards

made no allowances for differences in genetic make up in so far as it

affected bone age. As a result, the study rejected the adequacy of the

testing method and determined that new standards were thus required.

Despite this, the Australian Government continued to apply this

testing. Indeed, from September 2008 to January 2012, 208

people detained as members of smuggling crews who claimed to be minors

had been detained. After the result of X-ray testing, 86 of these

persons were determined to be adults, despite truly being minors. This

means, in effect, that Australia’s Government was advocating and

allowing the detention of children in adult prisons based on testing

that, anthropologically speaking, had been rejected almost a decade

prior.

A Senate inquiry ensued and a number of recommendations were

made. Whilst the Government generally accepted the recommendations

arising out of the majority report, it disagreed with all further

recommendations made by the Senate Committee, except for the funding of

Government funded legal agencies, such as Legal Aid, to assist

Indonesian minors detained and accused of people smuggling to return to

Indonesia in order to substantiate their age.

Of most concern regarding the outcome is that it took until 2013

before any amendments to crime regulations were made removing the use

of x-ray testing for age. Furthermore, the Human Rights Commission was

not consulted prior to implementing x-ray testing for age despite this

avenue being available to them.

There have remained ongoing issues arising from these events and this inquiry.

For example, there remains a significant issue for children detained

in circumstances where their age is not known, so far as legal

representation is concerned, particularly in relation to any criminal

proceedings arising from minors being detained on people smuggling

charges. Depending on how they plead to criminal offences, this can also

affect other recovery actions against the Government should there be

untoward treatment, such as detaining a minor in an adult prison and any

subsequent injury.

Furthermore, there is an ongoing fear that anyone pleading guilty to

such offences are doing so without adequate advice, legal

representation, or proper knowledge and understanding of the crimes in

which they are charged. Without ensuring this advice and access to a

proper defence it is clear that Australia will continue to advocate for

laws that allow for breaches of international treaties and procedural

fairness.

The point here is that there should be no excuse for delaying the

implementation of comprehensive rights based laws that advocate for the

rights of children. Nor should there be any politically motivated attack on a commission charged with protecting Human Rights in Australia.

What history confirms is that the current political landscape looks

to solve immigration and people smuggling policies with short term fixes

without implementing a longstanding agenda that creates a system

whereby Australia maintains its Human Rights obligations, yet maintains a

tough stance on people smuggling and national security issues.

Despite what the current government would have you think with their

mantra and partisan stance of “stop the boats”, this can be achieved by

ongoing consultation with Human Rights based groups, including the Human

Rights Commission.

From an international perspective, policies need to be shifted to

create a more collaborative approach internationally to shut down

illegal people smuggling operations. And more importantly, greater

education needs to be provided to the regions where the operators of the

boats that come to Australia are recruited.

Domestically, it seems that Australia is crying out for human rights

based legislation to be enacted to ensure that breaches of international

human rights are recognised at their earliest stage, not only by our

government when making laws, but also so that they are actionable should

they be breached.

It is clear there needs to be a complete overhaul of attitudes

amongst not only our members of Parliament but also their constituents.

There needs to be current and ongoing checks and balances and there

needs to be an underlying concern and motivation to ensure change not

only to minors held in detention centres but any minor that finds

themselves at the mercy of Australia’s current immigration policies.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

No comments:

Post a Comment