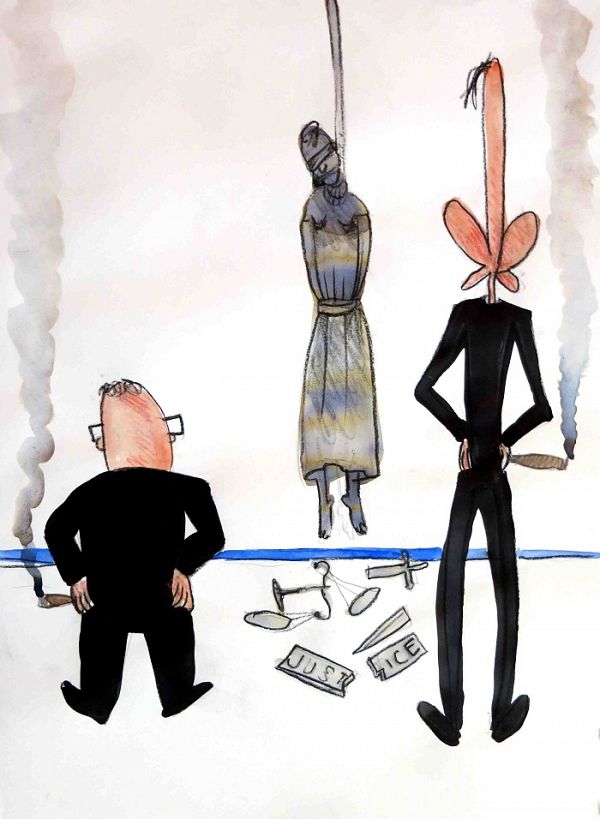

Refoulement most foul: Returning Tamils to their persecutors

The Abbott Government feel comfortable flouting the law in the silence of the high seas, but Dr Binoy Kampmark doesn't believe it will be able to maintain such secrecy in front of the High Court.

Immigration law exists in isolation in Australia.

At least, according to the Abbott Government this is the case.

Domestic considerations trump international obligations — unless they

pertain to security dictates from Washington or foreign states willing

to prevent future asylum seekers from reaching safety. The fate of a

particular group of people can be determined by “videolink” or “enhanced screening” at sea comprising a mere four questions.

This is clearly evident by the nature of the 153 Tamils who are set

for return after they left Pondicherry in southern India on June 13.

In what has become something of high seas drama, nothing has been

heard from the vessel since Saturday, June 28, when it was located 250

kilometres from Christmas Island.

Two boats, reported the BBC,

said to be carrying asylum seekers were found in the Indian Ocean, with

those from one vessel handed over to the Sri Lankan authorities.

Refugee activists claim that at least 11 on board had suffered torture

in Sri Lanka.

Refugee advocates have also sought to stifle moves by the Abbott

Government to transfer the rest of those on the intercepted vessels to

Sri Lanka.

The High Court on Monday granted an interim injunction halting the move and heard arguments on the matter today (Tuesday) before the matter was adjourned until the following day.

The vital argument in the case was made by Ron Merkel QC, who ventured to Justice Susan Crennan

that it would be illegal to have the asylum seekers returned as matters

stood because they were not having their claims properly assessed.

The murkiness of the case has been hampered by Immigration Minister

Scott Morrison’s refusal to comment on the matter, keeping his usual

near constipated approach about so-called “operational matters”. He is also in close contact with the government of President Mahinda Rajapaksa (and, indeed, is currently visiting Sri Lanka for a ceremony to formally hand over some patrol boats Australia gifted the regime last year).

Due to Morrison's stubborn reticence, it is unclear whether the

transfer has already taken place — though, by definition, that would

negate the strength of the High Court injunction as courts tend to get

frustrated when their jurisdiction is casually flouted.

Frustrating legal intentions has been the business of the Abbott Government since it came to office.

To be fair, though, the refugee agenda has generally been a case of

epic frustration for governments of all persuasions — so much so that Kevin Rudd suggested, as did the former Howard Government, that the UN Refugee Convention 1951

be modernised to fit a harder, non-compromising approach. If you don’t

want refugees, redraft the protocols — other, more sensible, regimes are

at least honest enough to avoid signing them.

Instead, an entire system resisting the application of the Refugee Convention has been established.

Asylum seekers are prevented from genuine processing by means of a

regional network of camps policed by privatised security firms.

Australia is deemed a legal void for the purposes of arrival by such

asylum seekers; those found to be genuine refugees are refused

resettlement in Australia.

When it comes to interception of a vessel at sea with asylum seekers,

we are seeing the same sort of flouting. The Australian Human Rights

Commission has taken a sound course on this, despite the problems posed by a lack of information on the vessel.

In one sense, this has suited Morrison to a tee — suffocate the line of information and stifle any revelations.

This demonstrates the classic fallacy — by not mentioning rights, so

as not to encourage them, in fact suggests they do not exist. By keeping

asylum seekers in the dark to keep the public in the dark and the

problem not so much goes away as ceases to be a legal one.

It becomes a political problem requiring Sri Lankan help.

The Commission has urged the Australian Government

to transfer asylum seekers intercepted at sea to the Australian

mainland, while providing them with information on their rights under

the Refugee Convention; rights to seek legal assistance; contact details

for legal aid and community legal centres, and independent monitoring

bodies such as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and the

Commonwealth Ombudsman. Access to interpreters and facilities such as

interview rooms is also encouraged (AHRC, 4 Jul).

Needless to say, none of these were available at sea. Such

recommendations read like fantasy before the corrosive and destructive

program of the Australian Government.

There is one vital issue that seems to elude Abbott and his colleagues – that of the cardinal principle of non-refoulement (Refugee Convention, Article 33).

There is enough jurisprudence,

legal disputation and policy on this to fill an entire legal library;

governments cannot return individuals to their country of origin where

they are expected to be prosecuted or face threats to life and liberty

on the basis of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or

membership of a particular social group.

Paul Power, CEO of the Refugee Council of Australia, said the issue could not have any higher stakes:

“For asylum seekers, this is a matter of life and death,

particularly in Sri Lanka which has a long history of political violence

on a scale unimaginable to Australians.”

A brutal civil war,

brought to a particularly brutal conclusion in 2009 by the Singhalese

dominated forces, has done nothing to reassure advocates about the fate

of returned Tamils — who, by the admission of Sri Lankan authorities, will face

“... rigorous imprisonment."

The problem here is compounded by difficulties in monitoring the fate of returnees.

There is something staggering about the conduct of the Australian Government concerning those on board the ill-fated vessel.

The High Court was absolutely correct to find that the case be heard

more thoroughly. The Abbott Government has characteristically sought to

avoid it.

It fits a broader picture of defiance — towing vessels without

Indonesian approval back to Indonesia and then adopting a principle of

non-denial when confronted with them.

But while the Government might remain silent at sea, it won’t find

such secrecy possible before the highest tribunal in the land.

Dr Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: bkampmark@gmail.com.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License

No comments:

Post a Comment